So far, we have discovered two principles for organizing the human sciences: the elements of these sciences (philosophy, the history of spirit, and systematics) and the two spiritual attitudes (autonomy and theonomy). In the center of the structure, however, stand the organization of the spiritual areas and the human sciences corresponding to these areas. The elements and the spiritual attitudes receive their content only in the objects of the human sciences. The organization of the spiritual area is based on the functions of the spirit-bearing gestalts. For to realize spirit means to subject these functions to validity. This has led to the view that the organizations of the areas of spirit must conform to the facilities of the soul, especially to the faculties of thought, volition, and feeling. This view is still found in Kant. But it cannot be carried out, for the organization of the psychic functions is quite uncertain, and the comprehension of the areas of meaning is, as an act of creative conviction, independent of such variations. Further, it is more difficult to make the number of areas of meaning correspond to the number of psychic functions--this is especially evident with regard to art and religion. Ultimately, all psychic faculties participate in every spiritual act; the soul is uniformly directed to the contexts of meaning. Psychic functions are not spiritual functions, though they are the existential form of spiritual functions.

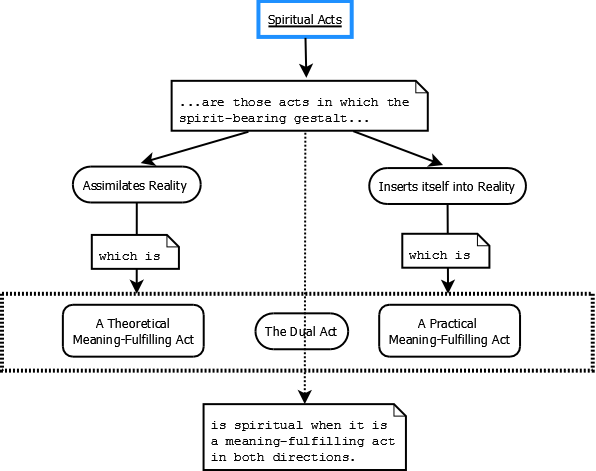

The individual gestalt becomes spirit-bearing when the universal, the thought form, is projected into this gestalt**—**that is, when the gestalt achieves freedom. Spiritual acts are those acts in which the individual gestalt establishes its relations to reality in freedom, or in a valid way. The dual act of every gestalt (i.e., the assimilation of reality and the insertion of itself into reality) is spiritual when it is a meaning-fulfilling act in both directions. The meaning-fulfilling act that assimilates reality is theoretical; the act that inserts itself into reality is practical. In the theoretical act, the spirit-bearing gestalt assimilates the forms of reality. The gestalt can contain things only as forms. Within the realm of being, however, things stand alongside things, gestalts alongside gestalts. In the practical act, the spirit-bearing gestalt establishes an existential relationship. But a free, meaning-fulfilling existential relationship is possible only between things that have assimilated the universal--that is between spirit-bearing gestalts. All other existential relationships lie in a prespiritual sphere of the gestalt and can attain spiritual significance only in an indirect way, as we have seen in our discussion of technology. The establishment of the universal thought relationship and of the universal existential relationship: this is the fundamental dual act of the spirit-bearing gestalt. It is an act that is the basis for the division of the spiritual areas into a theoretical and a practical series.